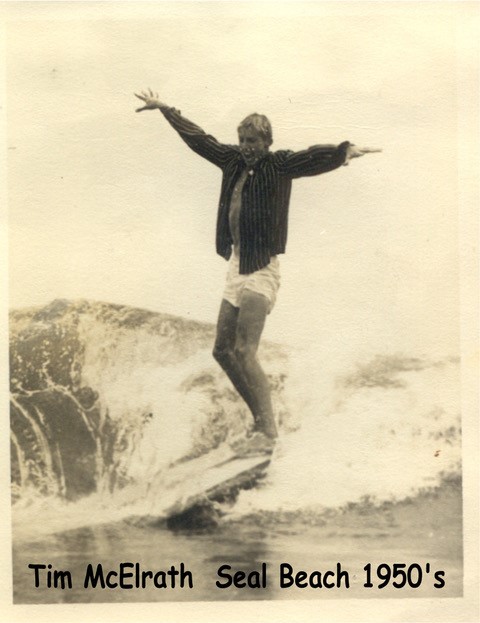

By Frank (Tim) McElrath

On the surface, growing up in Seal Beach during the World War II years seemed rather easy. However, below the surface, life was a bit more complex. Most of the kids had come from somewhere else. Seal Beach was a “bedroom” community. We lived at 1010 Seal Way. The beach in front of our house was the center of my life.

Our dads had gone off to the war and our moms worked for the war. We were, in a sense, the first group of “latch key kids.” My dad was in the South Pacific in the Sea Bees on Christmas Island and my mom worked at Douglas Aircraft as a courier. My two brothers and I fended for ourselves. We kept waiting for the Japanese to attack the Seal Beach Pier as there had been an attack up north on the Ventura coast. On bicycle, I sold newspapers to the servicemen.

All during WWII guys and gals would go off to war. It seemed that not a lot of innovation was taking place in the town to the North of the electric power plant. If you got off the bus there, coming back from Long Beach, you could save a dime. Also, out-of-town kids would be challenged there and turned back. Unfortunately, you weren’t generally brazen enough to pull off that maneuver. The South was bordered by Anaheim Landing and Highway 101 stopped all growth to the East which encompassed the Hellman Ranch. The Pacific Ocean blocked the West. So essentially we were living on an island.

The City of Seal Beach had one police car to cover the war period – roughly between 1942 and 1946. It was an old Buick Dynaflow and eventually had only one headlight and a clutch that moaned as it slipped. It had a pile of rattles and roans, and late at night you could hear the clutch for ten blocks away as you anticipated the arrival of the one-eyed monster. However, the police car did have a quiet advantage. The one-car force allowed us to always know where they were; we were actually faster and quicker on our bikes. Our sanctuary and safety -valve was to travel on our bikes down below the pier to the sun room next to the pier or along Seal Way. The old Dynaflow could travel to none of these places. The police car made so much noise they gave themselves away, and it was a sad day in 1946 when a new four-door Mercury police car parked in front of the station followed soon by another police car. Thus it became risky to jump off the pier, as the new police car had the capacity to catch you. The war ended, and our years of real or imagined escaping from the old police car ended. I can hear the many associated noises right now. That was 62 years ago!

Instead, we could always raid citizens’ fruit trees. The guy who owned the house on the corner of Fifth and Central had some great fruit trees. I vividly remember the summer he implanted the trip wires with the bells attached. Another summer he had lights that tripped on to expose us in the middle of the yard. The six foot fence was difficult to climb over, and being under pressure, I was never sure I could escape. I was pretty sure I could but didn’t want to test it.

God, that guy charged my heart with super exciting moments. He provided me with electrifying excitement for five years, hiding on my bike in the middle of the night, listening for the old police car, the Dynaflow. You know what? Fruit trees were scarce during World War II years. He didn’t catch me because I was too good. No, I don’t think he wanted to catch me either. It was truly his game. I should have paid him for all those thrills. I wondered if he were a returned War vet.

We all grew up to become the crop of the first Seal Beach surfers. We went from bikes to boards. Almost all of us started riding waves on surf mats.

In the 1940’s, prior to surf mat riding, we used pillowcases! We’d slip the slips, so to speak. Nylon was the case of choice. The technique was to hold the pillow open so it would fill with air, hold on tight to deep the case full, turn toward shore and ride your pillowcase toward shore, and then go back out to sea and do it again.

Seal Beach was a very windy place due to the Santa Ana Canyon Gap. The wind pulled or pushed as the land heated up from the ocean out to the desert beyond Palm Springs.

The Stangland family held the beach concessions for umbrella rentals and surf mats. Surf mats were hard to come by. You could work as an umbrella boy, but this meant you had to remain at your stand all day and didn’t have time to ride your mat.

So one alternative was to plead with the umbrella boy and do favors for him. You could also attempt to “borrow” a mat and get down to the surf and hope the Stangland brothers didn’t catch you. G. Stangland, the dad, was no one to mess with. How does one explain that he swiped or robbed the mat?

There was only, at that time, one place to ride the biggest waves in town, and that was out in front of the main Life Guard stand on the South side of the pier. The big summer swells would start pumping in late June, July, and August. It was referred to as the South Swell and was usually caused by a storm off of Mexico or even as far as New Zealand. The cry would go out, “Surf’s Up!” As the day progressed, you would do all you could to borrow a surf mat and paddle out in front of the main Life Guard stand and position yourself to ride the Wave of the Day.

A set of waves consisted of a group of waves coming in succession, often with each progressive wave growing larger. One could pick the wave of the set he was to ride with care. I don’t recall a female mat rider, but if I had known one, I would have surely married her!

People would line the beach and argue as to which wave in the set was the largest. A lot of status was gained from not backing out of a monster wave but rather paddling into the drop and heading down, then to shoot out in front of the wave. Then a tense wait followed by a rush when the whole wave broke over on top of you and a flooded rush of water covered you; you held on and hoped your mat did not buckle or you got bounced off. The critical point was when you got pushed down under and the foaming

water was churning as if you were inside a Bendix washing machine. Here, upper body strength was an advantage.

It was crucial that you prepared your mat for optimum efficiency in wave riding. You would begin by wetting the mat and keeping it in the shade. Next, inflate your mat to the point where it was hard as a brick. You didn’t want a flimsy mat to buckle under the pressure of a big wave. This I remember, there was a big wave, in a huge set, in the summer of 1945. I may have ridden the Wave of the Day on a pinched surf mat. We never had enough money for all the things we wanted in life. It’s probably just as well. I think we were lucky to have lived when we did.

Surfing in Seal Beach probably got its biggest push from Lloyd Murray, as early in his surf development, he acquired a good board that fit him well. He had a job as a Seal Beach Life Guard. Lloyd was also married, owned a car and worked at Douglas Aircraft as an engineer.

People liked to be around Lloyd. He was one of the major talkers in the Western hemisphere, as he could converse on any and all topics. Some questions from Lloyd: What do you think the length of the ride would be if you paddled in the title bore and rode the wake from the Bay of Fundy to Cape Sable? Do you think you could ride the wake of the Matson Liner from Pearl Harbor to San Pedro, California? Those surely would get and hold your attention.

Lloyd was the kind of surfer who would wait all morning for the largest wave, then scream and yell as he picked up the wave and rode with joy toward the beach. Lloyd had a major influence in the Seal Beach surfing world.

Lee Howard, Chief of the Police Department, was drawn to Lloyd and hired him as Life Guard Captain. Lloyd, in turn, gradually hired surfers for Guard positions as they made good watermen. He liked to cook horse meat steaks in the Life Guard stand and bought vast amounts for 25 cents a pound, boasting of the protein value.

On a cold, windy Sunday, we gathered at the Guard Stand late in the day. Lloyd started cooking an extra large quantity of horse meat. We were also running a set of cards in a game of Hearts. Almost no one remained on the beach. We closed off the upstairs portion of the Guard Stand in an effort to block the wind. All of a sudden, smoke and flames were shooting up everywhere. Lloyd had forgotten the Hibachi upstairs. The Guard Stand began to smoke and the flames spread. Lloyd shouted, “The last thing we want down here is the Seal Beach Fire Department. Get the fire out.” We filled all the empty bottles of Carlings Red Cap Ale or better known a “Green Death,” poured sand on the fire and extinguished it. Next we salvaged the horse meat steaks, put the meat in huge hunks of sourdough French bread and washed it down with some fine Burgundy wine. That large burned hole remained in the center of the top floor until the stand was moved to the North side of the pier and a new stand was built.

I can only say this about the Seal Beach Surfers. We almost never conformed to a majority value system. We just refused to conform and did whatever it took to get into the surf, which often meant breaking the rules. We were a cross between a Bohemian and a Native.

To be qualified as a Surfer back in the fifties, it was essential that you owned a surfboard. Harold Walker, after Lloyd Murray and Dick Thomas, was the first to acquire a board. Harry Schurch and Jack Haley were next in line. Harold was willing to loan his board. Ole Olson helped me shape an old board into a small fast one. Ole ended up building boards in Maui, Hawaii and is coming to Seal Beach for the upcoming Seal Beach Historical Society community meeting on September 25, 2008. Harold Walker owns Walker Foam and manufactures most of the blank surfboards in the Western United States. The deal today is this! Do you still paddle out to ride a wave? Are you still a surfer?

When the surf is up, news travels fast. It’s like the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill.

The day in history the largest break occurred in Seal Beach was in early January 1951. The waves started building up in the morning and were too huge for us to paddle out. Instead, we carried our boards out to the end of the pier, went to the rail, and threw our boards over the side.

Next we had to paddle farther out as the sets were often breaking far beyond the pier. The waves at times would break clear across the beach from the pier all the way to the Naval Ammunition Depot and at times broke under the pier, breaking the bottom of the planks above. It was hard to estimate the size of the waves. Maybe 20 feet, but I know a lot of people didn’t show up that day.

I saw Harry Schurch jump over the side and quickly catch a big wave beyond the end of the pier. He later broke his board in half when it crashed into the pier.

It took me a long time to catch a wave. When I got up, I didn’t want to fall off and lose my board. The sand up on the beach seemed solid and secure.

That was in the winter of ‘51, just a few years after the summer of ‘45 when I rode my mat on the Wave of the Day.

Although surfing in Seal Beach evolved rather slowly, today it is important to protect our oceans. I almost want to cry.

Frank Timothy McElrath passed away in 2011 at age 77. Below is his obituary.